Managing workflows with snakemake

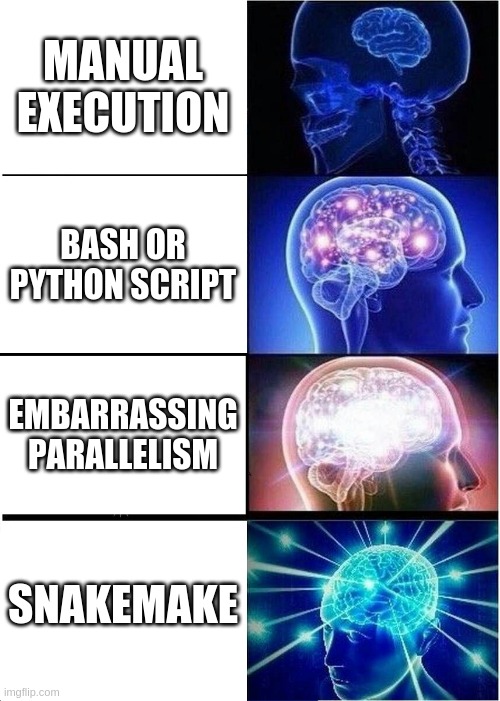

Lately I’ve been using Snakemake to manage analyses in my research. I’ve become a very enthusiastic proponent of it. I think more computational scientists should be aware of it. I wager Snakemake (or something like it) will eventually be a standard tool for data scientists.

In one sentence: Snakemake helps you glue your various bits of code into a unified DAG of compute jobs.

In this blog post I’ll describe what it is and how it makes a huge difference. You can find more detailed information about Snakemake in its documentation.

Motivation

A couple of questions computational scientists should think about:

- How do I more fully automate my work?

- How do I harness all of the compute power available to me?

Regarding question (1): self-automation is important for at least two reasons. It (i) increases your productivity and (ii) makes your work reproducible.

Question (2) hints at a notion of efficiency. Somehow, you need to map your compute workload onto the available CPUs. If your mapping doesn’t utilize all of the available resources, then you’re being wasteful. Your compute jobs take longer than necessary. Your research proceeds more slowly than it would otherwise.

Snakemake gives a clean answer to both questions.

Snakemake uses the insight that a typical computational workflow forms a DAG of compute jobs. That is, the nodes of the DAG are compute jobs; and the edges represent their dependencies on each other. There’s an edge from Job A to Job B iff Job B requires the output of Job A.

After constructing this DAG, Snakemake attempts to run as many jobs as possible in parallel. This is constrained by the jobs’ dependencies and the available compute resources.

If you’re on a workstation or server, Snakemake maps your jobs onto as many CPUs as you allow. Snakemake can also submit jobs to a cluster, if you have access to one. There is hardly any difference between running your workflow on a laptop or a supercomputer, from a UI standpoint.

Snakemake keeps track of intermediate results by looking for jobs’ output files. If the workflow gets interrupted for any reason, Snakemake can look at the intermediate results and pick up where it left off, minimizing redundant computation. Contrast this with a more old-fashioned scripting approach; if your script gets interrupted, then you probably have to find some kludgy way to avoid rerunning your whole workflow. Ask me how I know.

Snakemake: a quick, concrete description

People commonly describe Snakemake as “GNU make, plus Python syntax”.

Similar to make, the user defines their DAG using a set of rules.

A typical rule may look like this:

rule my_rule:

input:

"input_file_{protein}.csv"

output:

"output_file_{protein}.json"

resources:

threads=2,

mem_mb=100

shell:

"my_script {input} {output} --flag1 --flag2"

Roughly speaking, this rule

- requires an input file defined by the

inputblock; - creates an output file defined in the

outputblock; - demands CPU and memory defined in the

resourcesblock; - uses the terminal command specified in the

shellblock to perform the actual computation.

‘Wildcards’ in curly braces allow a single rule to define many compute jobs.

In our example, if another rule required output_file_EGFR.json and output_file_AMPK.json for its own inputs, then Snakemake would match EGFR and AMPK to the {protein} wildcard in my_rule and generate two distinct compute jobs – one for each protein.

It doesn’t appear in our example, but Snakemake augments this rule-based syntax with full Python syntax. For example, users can write Python functions that define a rule’s input, output, or resources. You can even import arbitrary Python modules. The resulting language is highly expressive, letting users define complex workflows.

I’ve given a small taste of Snakemake’s possibilities. I recommend Snakemake’s tutorials for a more detailed exposition.

Some examples

I used Snakemake to manage the analyses in my most recent project:

Sparse Signaling Pathway Sampling

The analyses entailed thousands of compute jobs and tens of thousands of CPU-hours. I used Snakemake to keep everything organized and to run all the jobs on a HTCondor cluster. With approximately 1000 CPUs, I complete all of the jobs in a little more than 24 hours.

I made an example Snakemake workflow for nested cross-validation:

Nested Cross-Validation demo

It has an origin story. More than a year ago, I needed to run a large nested cross-validation task. I used simple Python scripting, and relied on Scikit-learn’s built-in parallelism (i.e., Joblib). It was a major hassle. Joblib wasn’t clever enough to use all of the available CPUs, so the task took much longer than necessary. Sometimes a job would fail, and I’d have to figure out how to restart the workflow without rerunning everything. I wished there were a better way.

Months later when I learned about Snakemake, I immediately saw its value. It was exactly what I had wished for. I implemented the nested cross-validation workflow in a sort of catharsis.

\( \blacksquare\)